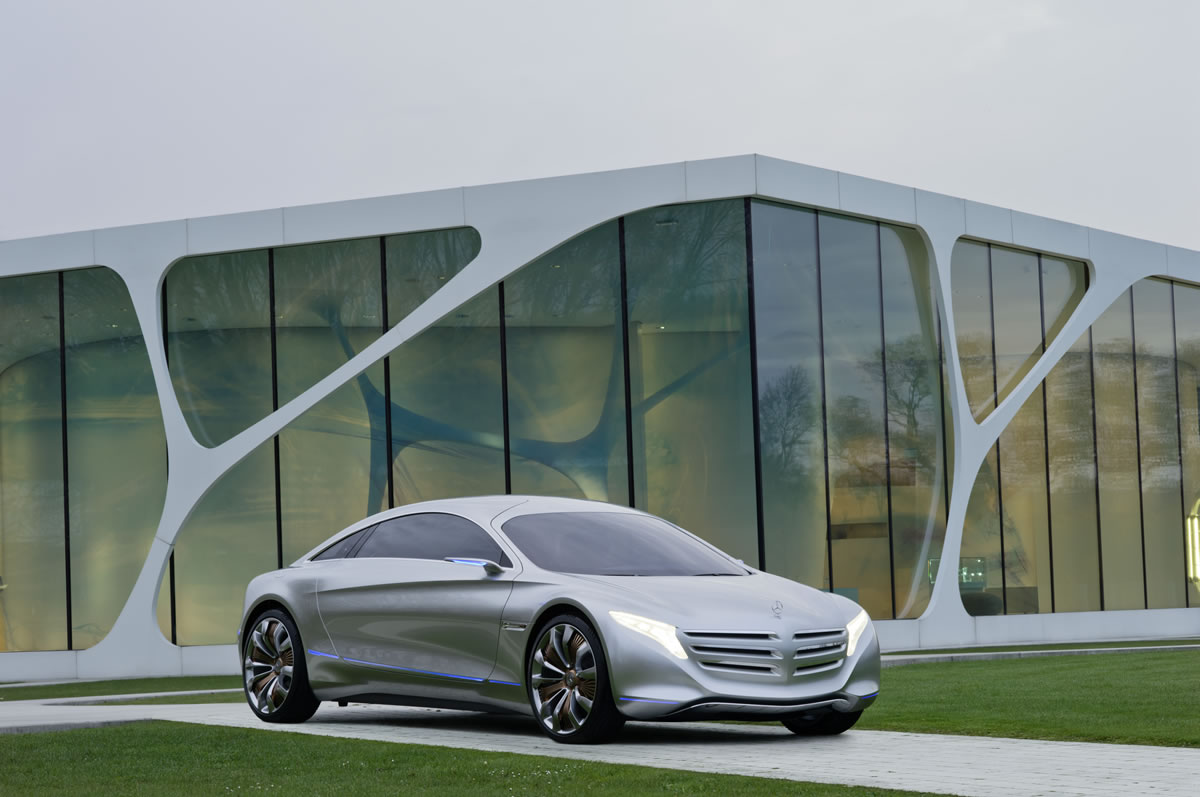

Imagine you’re driving down the 405, the turn signal clicks on and your Mercedes S-Class accelerates to 65 mph as it changes into the left lane passing two slower vehicles, all while you’re focused on the latest New York Times best seller. Once arriving at your destination, your self-driving car finds a parking space, drops you off and with the push of an electronic key, parks itself in the space.

On your way home, you hit rush hour, but your S-Class keeps a safe and continuous distance in stop-and-go traffic, minimizing your accident risk and letting you focus on your phone call. Your S-Class then effortlessly finds its way home through the dense traffic of the city, navigating it’s way around other cars, trucks, buses, bicyclists and pedestrians, all unpredictable and moving at their own pace. In reduced traffic areas the Mercedes adheres to the prescribed walking pace because it can read traffic signs and thanks to radar sensors and stereo cameras it can also keep an eye on pedestrians.

This is the future of driving, this is autonomous driving.

Up until a few years ago engineers and computer scientists and movie directors developed such science fiction scenarios to provide a visionary outlook of the mobility of the 21st century. Think back to movies like Demolition Man or Minority Report. Thanks to the innovations from Mercedes, reality is catching up with those movies, all the driving described above are already possible and are being tested under real-life conditions with the help of the latest assistance systems from Mercedes-Benz. At the same time researcher and development engineers from electronics companies, automotive suppliers and universities are working on intelligent hardware and software intended to gradually make the vehicles autonomous.

Consequently, everyday life will face a profound revolution. Even though the vision of autonomous driving goes back many decades, it is only now that the combination of steadily increasing computing power, innovations in the area of sensor technology and the scanning of a vehicle’s surroundings paired with the rapid digitisation and networking of everyday life makes driverless mobility attainable. There are many possibilities to enhance traffic safety, to make mobility more efficient and environmentally compatible and to create unimaginable freedoms for all road users. However, before the goal of highly or even fully autonomous driving is reached, several development obstacles must be overcome in order to make the hardware and software faster, more intelligent and more affordable. At the same time the infrastructure, legislative bodies and society will have to prepare for this new dimension of motoring.

“Autonomous driving will gradually become reality”, states Ralf Guido Herrtwich, Head of Driving Assistance and Chassis Systems in Group Research and Advanced Engineering at Daimler. “Initially we will drive autonomously on certain classes of roads, starting with the freeways and maybe only under certain weather or lighting conditions. In the beginning the system will also have to be monitored rather than grabbing a book and tuning out completely.”

Herrtwich warns that placing too high an expectation on autonomous vehicles that manage without any human intervention would be dangerous. At slow speeds, in stop-and-go traffic or in parking situations, driverless mobility is just a few years away. But, at high speeds and in complex situations it will be necessary for the driver to be involved for at least the next ten years. Assistance systems already on the market have shown that partly autonomous vehicles are capable of lowering the amount of accidents by compensating for human errors and reacting faster than humanly possible.

Driving assistance systems, like the ones on the new 2014 Mercedes S-Class and others found as standard equipment on Mercedes-Benz models play a crucial role in autonomous driving. These technologies are responsible for merging comfort and safety, they include DISTRONIC PLUS proximity control, which keeps the desired distance from the vehicle travelling ahead. In addition, the STEER CONTROL steering assistance system, for example in the new Mercedes-Benz E- and S-Class, keeps the vehicle in the centre of the lane. However, drivers need to keep their hands on the steering wheel at all times. Active Lane Keeping Assist can intervene when the driver unintentionally crosses a dotted line and the adjacent lane is occupied. The previous generation of the lane-keeping assistance system was already capable of detecting when a solid line was crossed. BAS PLUS Brake Assist with Cross-Traffic Assist cannot only prevent rear-end collisions, but can also intervene in the event of impending collisions with crossing traffic at junctions, if need be even including a full emergency stop. The latest version can now recognise pedestrians walking in front of the vehicle, warn the driver visually and audibly or in emergency situations even initiate autonomous braking.

These intelligent systems are made possible by an array of sensors that provide the vehicle with a 360-degree view of what is going on. Radar sensors of different ranges can “see” for a distance of up to 200 metres. Their input is complemented by a stereo camera behind the windscreen. Thanks to its two eyes, the camera can see a three-dimensional image of the area up to about 50 metres in front of the car and from there on – similar to human eyes to infinity – two-dimensionally.

All the data constantly streaming in are processed by various on-board systems, for instance, to calculate the trajectory of crossing vehicles or a pedestrian in anticipatory fashion, “read” traffic signs and issue appropriate warnings or initiate reactions. This makes it possible, for example, to let a vehicle drive or even autonomously overtake other vehicles safely at high speeds with the Mercedes-Benz Motorway Pilot system that has already undergone successful testing under real-life conditions.

Ideally autonomous automobiles equipped with the necessary sensor package, detailed map data and sufficient computing power can travel virtually any arbitrary route. One of the milestones for autonomous driving was the DARPA Grand Challenge, which was organised by the research and development branch of the US Department of Defense in the desert of Nevada in 2004 and 2005. Only on the second try did some of the expensive and hair-raisingly retrofitted vehicles manage to complete the route that stretched over 240 kilometres of very rough terrain.

“These two competitions inspired an entire research community that went to work with passion. This led to a quantum leap in technology, for sensors as well as applications. It is astonishing how far we have come this past decade”, says William “Red” Whittaker, professor of robotics at Carnegie Mellon University (CMU) in Pittsburgh and, together with his team, one of the DARPA winners. Pioneers like Whittaker also know about the obstacles the researchers and engineers still have to eliminate. Firstly there is the question of when the necessary technology will be powerful, compact and affordable enough to have the required potential for series production. The LIDAR laser scanners used for instance in Google’s driverless cars are too expensive for series-production use. Such precision mechanics that constantly rotate on the roof provide a detailed 360-degree view of the surroundings. But they cost several times the value of the cars on which they are mounted.

“Many of the hardware and software components are still too expensive. They are plainly and simply unaffordable for normal consumers. If I had that much money, I’d buy a great sports car and drive myself”, jokes Emilio Frazzoli, professor of aerospace engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), who normally deals with autonomous vehicles travelling by land or air.

This is why Daimler researchers like Ralf Guido Herrtwich are trying to offer an intelligently assembled array of radar sensors and cameras that collects the required information even without costly lasers in order to travel safely, efficiently and comfortably. “This technology ultimately mustn’t cost any more than today’s driving assistance systems, that is to say, a couple of thousand euros”, Herrtwich stresses. This also includes a continuously updated digital map that provides significantly more detail and may also remain more up to date than those of conventional navigation systems. Otherwise an autonomous vehicle will flounder if it encounters a new, non-registered construction zone or a recorded bend that deviates from the values measured by the on-board sensors. However, vehicles can assist each other in creating such new real-time maps because theoretically every car is able to record the route it travels and to feed the route data into databases.

Experts like CMU professor Whittaker expect autonomous vehicles to see the world differently. Their navigation aids have little in common with the combination of conventional maps and superimposed images we know from today’s assistance systems. “We are already able to create three-dimensional models of our environment that are better and more detailed than the human eye would ever be able to perceive”, says Whittaker of the initial prototypes. Such super-realistic models of the environment are generated partly on board and – thanks to mobile broadband access to the internet in future vehicles – partly in the Cloud.

Not only the vehicles need to evolve, the surrounding infrastructure does as well. Companies like Daimler have long researched so-called car-to-x communications that allow vehicles to exchange data with each other and their surroundings, including road signs and traffic cameras mounted above the road.

In April the Los Angeles metropolitan area became the first city in the world to synchronise all its 4500 traffic lights. Magnetic sensors in the road and hundreds of cameras feed their data into a central computer that dynamically controls all traffic lights to speed up the traffic flow of seven million daily commuters. During rush hour the system can phase the traffic lights only for bus lanes while other vehicles have to wait. “Especially for driving in an urban area surrounded by hundreds of thousands of other vehicles we already have a wealth of information as well as the infrastructure for lowering the costs and complexity of autonomous driving”, MIT researcher Frazzoli reflects. “A car can use its surroundings and other vehicles for its eyes and ears”.

Besides all the technical advances that are happening rapidly this also requires another change that has already begun. Society at large and legislative bodies have to rethink what constitutes the nature of a vehicle and of the modern transportation system overall. Because what would be possible technically is frequently legally impermissible. The Vienna Convention on Road Traffic from 1968 determines who may steer a car: “Every driver must have control of his vehicle at all times or be able to lead his animals”. Nobody thought of a computer of whatever kind at the wheel 45 years ago. And thus questions about certification and insurance as well as liability in the event of accidents are still a grey area.

Some legislators have tackled the issue. The US states of Nevada, California and Florida were the first to pass laws that govern the certification and operation of autonomous automobiles. This provides an incentive to companies to test their prototypes there and serves as a role model for one of the world’s largest automobile markets. Should the US establish national rules for autonomous vehicles, the EU and China would soon follow suit. Until then, autonomous driving will continue to be relegated to narrowly defined areas of application where people may never really take their hand and eyes off the steering wheel.

“We build all the systems in a way that ensure the driver regains full control the moment he or she wants to take over. Our systems are fully dedicated to providing support and relief”, says Daimler researcher Herrtwich. In his mind the transition from partly to fully autonomous systems is not only a matter of the technical capabilities of the systems, but goes hand in hand with the driver’s growing trust. “Once you personally experience that such a system works, then you trust it in more and more situations.“

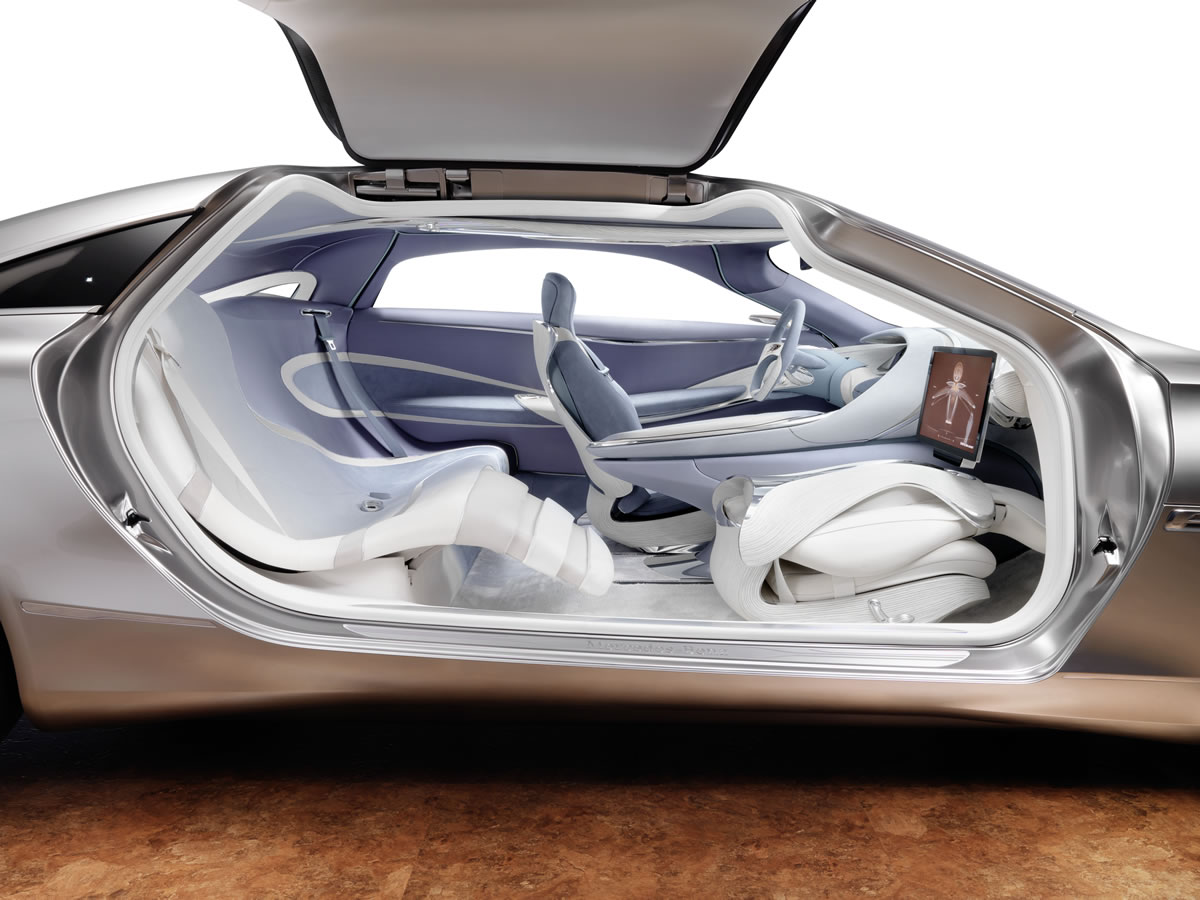

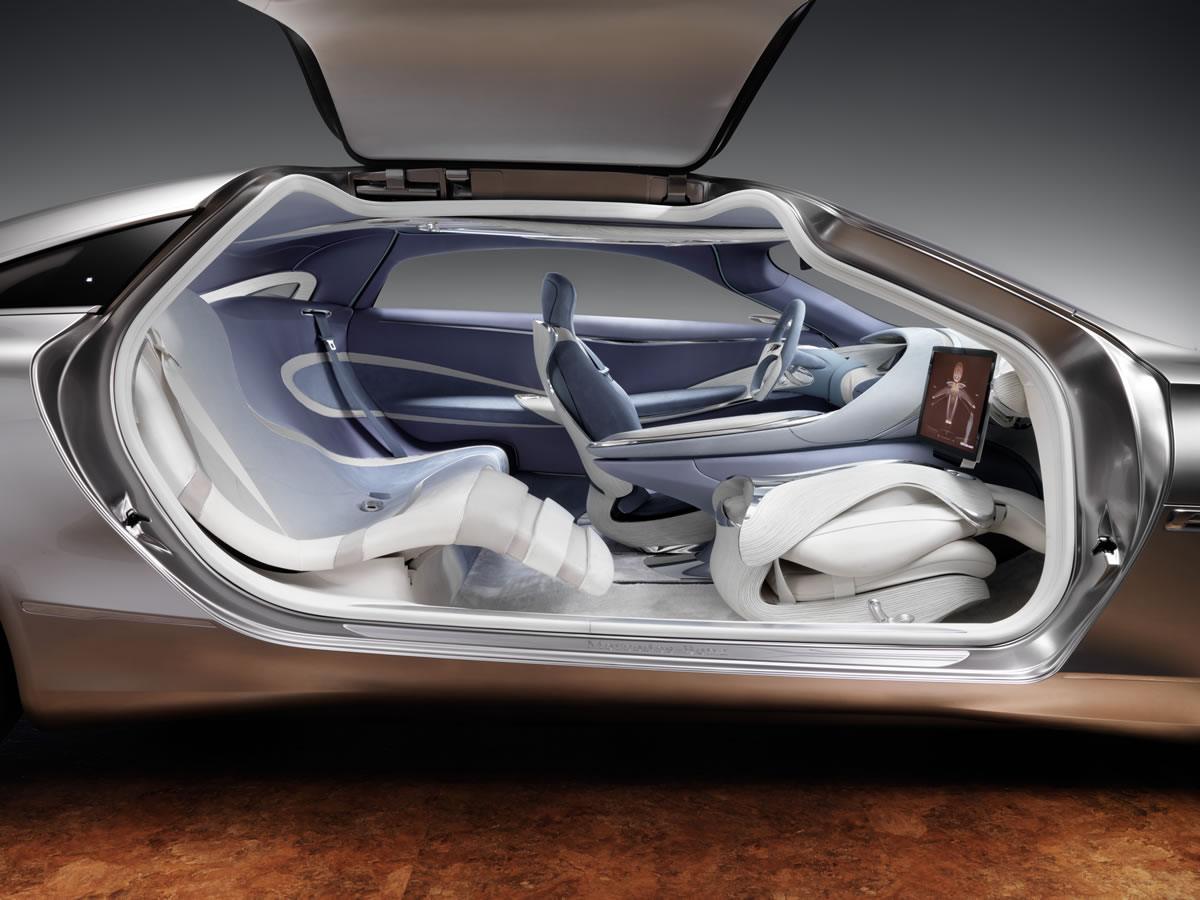

That is precisely what people seem to do if they are members of the group called ‘digital natives’, that is to say, all those who grew up surrounded by digital devices and services and in many cases willingly and completely count on technology. They hope that autonomous vehicles will relieve them of performing tedious routine tasks, such as commuting to and from work. People who try to talk on the phone, write something on their smartphone or even read their emails while driving will mostly be thrilled by the prospect of soon leaving the driving largely to the vehicle. The designers are already sketching driver’s seats for concept vehicles that swivel to let drivers direct their attention to a tablet computer or the newspaper instead of watching traffic.

Many senior citizens will also put their hope in the next vehicle generation or the one after that because their sensor systems and algorithms can make up for their own declining abilities. This promises to increase the mobility radius for millions of people who previously had been severely limited by old age, illness or disability.

Against this background it is understandable that Google promotes the prototypes of its autonomous vehicles with a video showing a blind man regaining his mobility thought to have been long lost. “For people with disabilities and senior citizens autonomous driving is a question of human dignity”, robotics researcher Whittaker believes. “For that we by no means need vehicles that drive autonomously under all conditions”. He envisions fully automatic people mover systems for public transportation, such as are already in existence at many airports. And some local authorities are considering their use in inner cities.

Autonomous driving also creates new freedoms in a much wider sense. For MIT professor Frazzoli, for instance, it is not about automatically steered vehicles that drive occupants from Point A to Point B, but about the opportunity to reinvent the transportation system and make it more efficient. “Today our cars are only utilised 5 to 10 per cent. The rest of the time they sit around. That is not a sustainable model”, says the scientist working in Singapore. “That’s why I believe that the ‘sharing economy’ and autonomous driving are two sides of the same coin”. ‘Sharing economy’ refers to a culture of sharing services and objects.

Instead of waiting for all-capable fully autonomous vehicles to arrive, says Frazzoli, carsharing services should be outfitted with vehicles that have a limited list of capabilities, such as finding the way to the nearest filling or charging station, picking up a waiting customer at a specific address, or if needed moving to another location. Such cars would solve several problems of autonomous driving at once, the scientist argues: “Since they’re driving without human passengers, they can always take the easiest route, for example, like a municipal commercial vehicle they could initially drive slowly at the edge of the road, and even if their steering and braking manoeuvres were a bit jerky, it wouldn’t bother any occupants. “In this way it is possible to lower the requirements on autonomous vehicles and at the same time expand their fields of application”. With growing experience the autonomous carsharing fleet could increase its effective radius.

There is still the question of how people at the wheel will come to terms with vehicles that act ever more independently. Experts agree that for the foreseeable future there will be mixed operations: some of the vehicles will be steered by people, while others drive partly or highly autonomously. Vehicles will enter and exit parking spaces at the push of a button. Or learn an oft-travelled route to derive independent actions therefrom. The urban infrastructure will increasingly exchange data with the road users. But at the same time there will be older vehicles on the road that have a lot less electronics and intelligence.

To William Whittaker this interaction of man and machine is not a problem. “When we drive on the motorway, we don’t have any direct contact with other drivers even at high speeds. You observe and interpret the behaviour of other road users. This works for all kinds of driving situations without having to draw a distinction between man and machine. Only one thing is for sure: autonomous driving is already a done deal today and will continue to advance steadily”. Via: Daimler